A wonderful article by Yale professor Paul Bloom on imagination:

Our main leisure activity is, by a long shot, participating in experiences that we know are not real. When we are free to do whatever we want, we retreat to the imagination—to worlds created by others, as with books, movies, video games, and television (over four hours a day for the average American), or to worlds we ourselves create, as when daydreaming and fantasizing. While citizens of other countries might watch less television, studies in England and the rest of Europe find a similar obsession with the unreal.

Another portion talks about emotional response:

The emotions triggered by fiction are very real. When Charles Dickens wrote about the death of Little Nell in the 1840s, people wept—and I’m sure that the death of characters in J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series led to similar tears. (After her final book was published, Rowling appeared in interviews and told about the letters she got, not all of them from children, begging her to spare the lives of beloved characters such as Hagrid, Hermione, Ron, and, of course, Harry Potter himself.) A friend of mine told me that he can’t remember hating anyone the way he hated one of the characters in the movie Trainspotting, and there are many people who can’t bear to experience certain fictions because the emotions are too intense. I have my own difficulty with movies in which the suffering of the characters is too real, and many find it difficult to watch comedies that rely too heavily on embarrassment; the vicarious reaction to this is too unpleasant.

The essay is based on an excerpt of his book, How Pleasure Works: The New Science of Why We Like What We Like, which looks like a good read if I could clear out the rest of the books on my reading pile.

A reading pile that, of course, contains too little fiction.

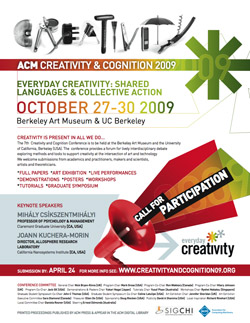

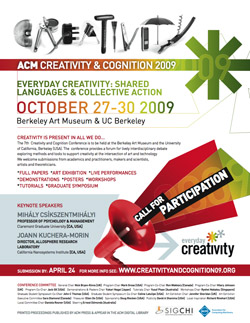

Passing along a call for the ACM Creativity & Cognition 2009. Sadly I’m overbooked and won’t be able to participate this year, but I attended in 2007 and found it a much more personal alternative to the more enormous ACM conferences (CHI, SIGGRAPH) without losing quality.

Everyday Creativity: Shared Languages and Collective Action

October 27-30, 2009, Berkeley Art Museum, CA, USA

Sponsored by ACM SIGCHI, in co-operation with SIGMM/ SIGART [pending approval]

Keynote Speakers

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi

Professor of Psychology & Management, Claremont Graduate University, USA

JoAnn Kuchera-Morin

Director, Allosphere Research Laboratory, California Nanosystems Institute, USA

Jane Prophet

Professor of Interdisciplinary Computing, Goldsmiths University of London, UK

Call for Participation

Full Papers, Art Exhibition, Live Performances, Demonstrations, Posters, Workshops, Tutorials, Graduate Symposium

Submission deadline: April 24, 2009

For more information and submission process see: www.creativityandcognition09.org

Creativity is present in all we do. The 7th Creativity and Cognition Conference (CC09) embraces the broad theme of Everyday Creativity. This year the conference will be held at the Berkeley Art Museum (CA, USA), and asks: How do we enable everyone to enjoy their creative potential? How do our creative activities differ? What do they have in common? What languages can we use to talk to each other? How do shared languages support collective action? How can we incubate innovation? How do we enrich the creative experience? What encourages participation in everyday creativity?

Creativity is present in all we do. The 7th Creativity and Cognition Conference (CC09) embraces the broad theme of Everyday Creativity. This year the conference will be held at the Berkeley Art Museum (CA, USA), and asks: How do we enable everyone to enjoy their creative potential? How do our creative activities differ? What do they have in common? What languages can we use to talk to each other? How do shared languages support collective action? How can we incubate innovation? How do we enrich the creative experience? What encourages participation in everyday creativity?

The Creativity and Cognition Conference series started in 1993 and is sponsored by ACM SIGCHI. The conference provides a forum for lively interdisciplinary debate exploring methods and tools to support creativity at the intersection of art and technology. We welcome submissions from academics and practitioners, makers and scientists, artists and theoreticians. This year’s broad theme of Everyday Creativity reflects the new forms of creativity emerging in everyday life, and includes topics of:

- Collective creativity and creative communities

- Shared languages and Participatory creativity

- Incubating creativity and supporting Innovation

- DIY and folk creativity

- Democratising creativity

- New materials for creativity

- Enriching the collaborative experience

We welcome the following forms of submission:

- Empirical evaluations by quantitative and qualitative methods

- In-depth case studies and ethnographic analyses

- Reflective and theoretical accounts of individual and collaborative practice

- Principles of interaction design and requirements for creativity support tools

- Educational and training methods

- Interdisciplinary methods, and models of creativity and collaboration

- Analyses of the role of technology in supporting everyday creativity

The Berkeley Art Museum should be a great venue too.

Given some number of talented people, success is not particularly surprising. But sustaining that success in a creative organization, the way that Pixar has over the last fifteen years is truly exceptional. Ed Catmull, cofounder of Pixar (and computer graphics pioneer) writes about their success for the Harvard Business Review:

Given some number of talented people, success is not particularly surprising. But sustaining that success in a creative organization, the way that Pixar has over the last fifteen years is truly exceptional. Ed Catmull, cofounder of Pixar (and computer graphics pioneer) writes about their success for the Harvard Business Review:

Unlike most other studios, we have never bought scripts or movie ideas from the outside. All of our stories, worlds, and characters were created internally by our community of artists. And in making these films, we have continued to push the technological boundaries of computer animation, securing dozens of patents in the process.

On Creativity:

People tend to think of creativity as a mysterious solo act, and they typically reduce products to a single idea: This is a movie about toys, or dinosaurs, or love, they’ll say. However, in filmmaking and many other kinds of complex product development, creativity involves a large number of people from different disciplines working effectively together to solve a great many problems. The initial idea for the movie—what people in the movie business call “the high concept”—is merely one step in a long, arduous process that takes four to five years.

A movie contains literally tens of thousands of ideas.

On Taking Risks:

…we as executives have to resist our natural tendency to avoid or minimize risks, which, of course, is much easier said than done. In the movie business and plenty of others, this instinct leads executives to choose to copy successes rather than try to create something brand-new. That’s why you see so many movies that are so much alike. It also explains why a lot of films aren’t very good. If you want to be original, you have to accept the uncertainty, even when it’s uncomfortable, and have the capability to recover when your organization takes a big risk and fails. What’s the key to being able to recover? Talented people!

Reminding us that we learn more from failure, the more interesting part of the article talks about how Pixar responded to early failures in Toy Story 2:

Toy Story 2 was great and became a critical and commercial success—and it was the defining moment for Pixar. It taught us an important lesson about the primacy of people over ideas: If you give a good idea to a mediocre team, they will screw it up; if you give a mediocre idea to a great team, they will either fix it or throw it away and come up with something that works.

Toy Story 2 also taught us another important lesson: There has to be one quality bar for every film we produce. Everyone working at the studio at the time made tremendous personal sacrifices to fix Toy Story 2. We shut down all the other productions. We asked our crew to work inhumane hours, and lots of people suffered repetitive stress injuries. But by rejecting mediocrity at great pain and personal sacrifice, we made a loud statement as a community that it was unacceptable to produce some good films and some mediocre films. As a result of Toy Story 2, it became deeply ingrained in our culture that everything we touch needs to be excellent.

On mixing art and technology:

[Walt Disney] believed that when continual change, or reinvention, is the norm in an organization and technology and art are together, magical things happen. A lot of people look back at Disney’s early days and say, “Look at the artists!” They don’t pay attention to his technological innovations. But he did the first sound in animation, the first color, the first compositing of animation with live action, and the first applications of xerography in animation production. He was always excited by science and technology.

At Pixar, we believe in this swirling interplay between art and technology and constantly try to use better technology at every stage of production. John coined a saying that captures this dynamic: “Technology inspires art, and art challenges the technology.”

I saw Catmull speak to the Computer Science department a month or two before I graduated from Carnegie Mellon. Toy Story had been released two years earlier, and 20 or 30 of us were all jammed into a room listening to this computer graphics legend speaking about…storytelling. The importance of narrative. How the movies Pixar was creating had less to do with the groundbreaking computer graphics (the reason that most were in the room) than it did with a good story. This is less shocking nowadays, especially if you’ve ever seen a lecture by someone from Pixar, but the scene left an incredible impression on me. It was a wonderful message to the programmers in attendance about the importance of placing purpose before the technology, but without belitting the importance of either.

(While digging for an image to illustrate this post, I also found this review of The Pixar Touch: The Making of a Company, a book that seems to cover similar territory as the HBR article, but from the perspective of an outside author. The image is stolen from Ricky Grove’s review.)

Creativity is present in all we do. The 7th Creativity and Cognition Conference (CC09) embraces the broad theme of Everyday Creativity. This year the conference will be held at the Berkeley Art Museum (CA, USA), and asks: How do we enable everyone to enjoy their creative potential? How do our creative activities differ? What do they have in common? What languages can we use to talk to each other? How do shared languages support collective action? How can we incubate innovation? How do we enrich the creative experience? What encourages participation in everyday creativity?

Creativity is present in all we do. The 7th Creativity and Cognition Conference (CC09) embraces the broad theme of Everyday Creativity. This year the conference will be held at the Berkeley Art Museum (CA, USA), and asks: How do we enable everyone to enjoy their creative potential? How do our creative activities differ? What do they have in common? What languages can we use to talk to each other? How do shared languages support collective action? How can we incubate innovation? How do we enrich the creative experience? What encourages participation in everyday creativity?