I was reminded this morning that Mario Manningham, a wide receiver who played for Michigan was rumored to have scored a 6 (out of 50) on the Wonderlic, an intelligence test administered in some occupations (and now pro football) to check the mental capability of job candidates. Intelligence tests are strange beasts, but after watching my niece working on similar problems—for fun—during her summer vacation last week, the tests caught my eye more than when I first heard about it.

Manningham was once a promising undergrad receiver for U of M, but has in recent years proven himself to be a knucklehead, loafing through plays and most recently making headlines for marijuana use and an interview on Sirius radio described as “… arrogant and defensive. When asked about the balls he dropped in big spots, he responded, ‘What about the ball I caught?’” So while an exceptionally low score on a standardized test might suggest dyslexia, the guy’s an egotistical bonehead even without mitigating factors.

Most people don’t associate brains with football, but in recent years teams have begun to use a Wonderlic test while scouting, which consists of 50 questions to be completed in 12 minutes. Many of the questions are multiple choice, but the time is certainly a factor when completing the tests. A score of 10 is considered “literate”, while 20 is said to coincide with average intelligence (an IQ of 100, though now we’re comparing one somewhat arbitrary numerically scored intelligence test with another).

In another interesting twist, the test is also administered to players the day of the NFL combine—which means they first spend the day running, jumping, benching, interviewing, and lots of other -ings, before they sit down and take an intelligence test. It’s a bit like a medical student running a half marathon before taking the boards.

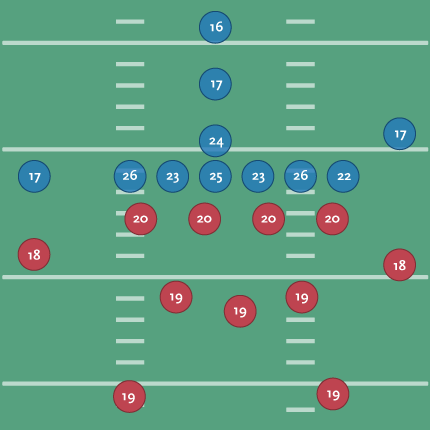

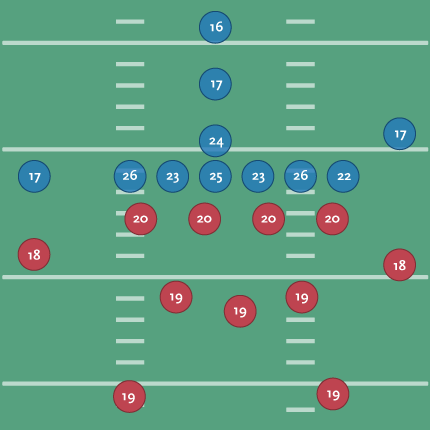

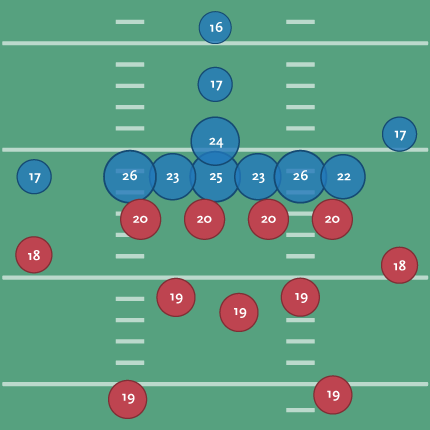

Wonderlic himself says that basically, the scores decrease as you move further away from the ball, which is interesting but unsurprising. It’s sort of obvious that a quarterback needs to be on the smarter side, but I was curious to see what this actually looked like. Using this table as a guide, I then grabbed this diagram from Wikipedia showing a typical formation in a football game. I cleaned up the design of the diagram a bit and replaced the positions with their scores:

Offense is shown in blue, defense in red. You can see the quarterback with a 24, the center (over 6 feet and around 300 lbs.) averaging higher at 25, and the outside linemen even a little higher. Presumably this is because the outside linemen need to mentally quick (as well as tough) to read the defense and respond to it. Those are the wide receivers (idiot loud mouths) with the 17s on the outside.

(For people not familiar with American Football, the offense and defense are made up of totally separate sets of players. I once showed this piece to a group who stared at me blankly, wondering how someone's IQ could change mid-game.)

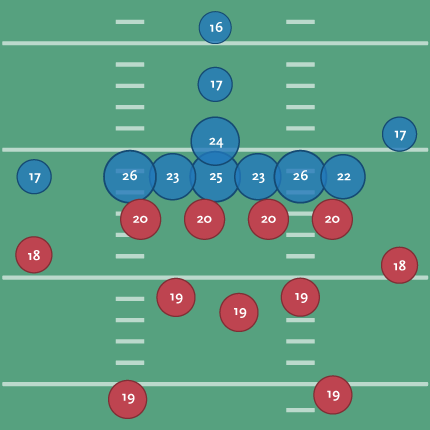

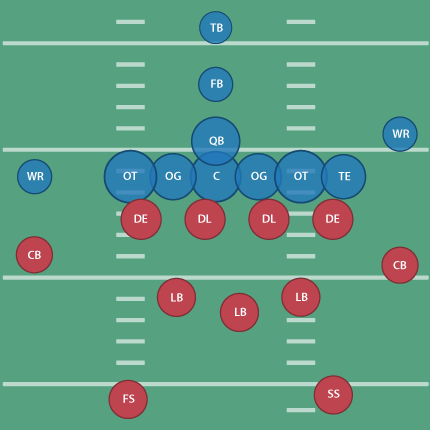

To make the diagram a bit clearer, I scaled each position based on its score:

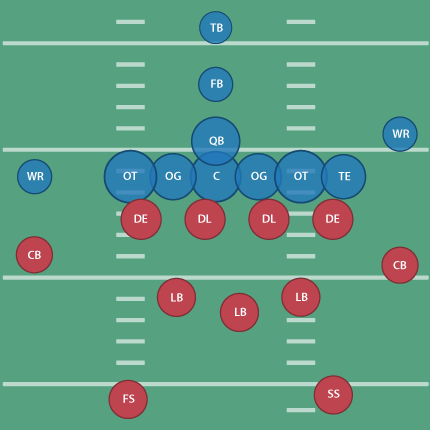

That’s a little better since you can see the huddle around the ball and where the brains need to be for the system of protection around it. With the proportion, I no longer need the numbers, so I’ve switched back to using the initials for each position’s title:

(Don’t tell Tufte that I’ve used the radius, not the proportional area, of the circle as the value for each ellipse! A cardinal sin that I’m using in this case to improve proportion and clarify a point.)

I’ll also happily point out that the linemen for the Patriots all score above average for their position:

| Player |

Position |

Year |

Score |

| Matt Light |

left tackle |

2001 |

29 |

| Logan Mankins |

left guard |

2005 |

25 |

| Dan Koppen |

center |

2003 |

28 |

| Stephen Neal |

right guard |

2001 |

31 |

| Nick Kaczur |

right tackle |

2005 |

29 |

A position-by-position image for a team would be interesting, but I’ve already spent too much time thinking about this. The Patriots are rumored to be heavy on brains, with Green Bay at the other end of the spectrum.

An ESPN writeup about the test (and testing in general) can be found here, along with a sample test here.

One odd press release from Wonderlic even compares scores per NFL position with private sector job titles. For instance, a middle linebacker scores like a hospital orderly, while an offensive tackle is closer to a marketing executive. Fullbacks and halfbacks share the lower end with dock hands and material handlers.

During the run-up to Super Bowl XXXII in 1998, one reporter even dug up the Wonderlic scores for the Broncos and Packers, showing Denver with an average score of 20.4 compared to Green Bay’s 19.6. As defending champions, the Packers were favored but wound up losing 31-24.

Nobody cited test scores in the post-game coverage.