Obscenity law in the United States is based on Miller vs. California, a precedent set in 1973:

“(a) whether the ‘average person, applying contemporary community standards’ would find that the work, taken as a whole, appeals to the prurient interest,

(b) whether the work depicts or describes, in a patently offensive way, sexual conduct specifically defined by the applicable state law, and

(c) whether the work, taken as a whole, lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value.”

Of course, the definition of an average person or community standards isn’t quite as black and white as most Supreme Court decisions. In a new take, the lawyer defending the owner of a pornography site in Florida is using Google Trends to produce what he feels is a more accurate definition of community standards:

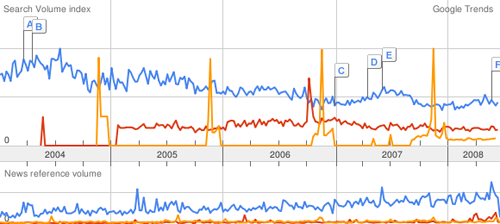

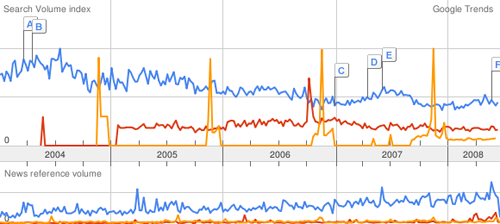

In the trial of a pornographic Web site operator, the defense plans to show that residents of Pensacola are more likely to use Google to search for terms like “orgy” than for “apple pie” or “watermelon.” The publicly accessible data is vague in that it does not specify how many people are searching for the terms, just their relative popularity over time. But the defense lawyer, Lawrence Walters, is arguing that the evidence is sufficient to demonstrate that interest in the sexual subjects exceeds that of more mainstream topics — and that by extension, the sexual material distributed by his client is not outside the norm.

Below, “surfing” in blue, “orgy” in red, and “apple pie” in orange:

A clever defense. The trends can also be localized to roughly the size of a large city or county, which arguably might be considered the “community.” The New York Times article continues:

“Time and time again you’ll have jurors sitting on a jury panel who will condemn material that they routinely consume in private,” said Mr. Walters, the defense lawyer. Using the Internet data, “we can show how people really think and feel and act in their own homes, which, parenthetically, is where this material was intended to be viewed,” he added.

Fascinating that there could actually be something even remotely quantifiable about community standards. “I know it when I see it” is inherently subjective, so is any introduction of objectivity an improvement? For more perspective, I recommend this article from FindLaw, which describes the history of “Movie Day” at the Supreme Court and the evolution of obscenity law.

The trends data has many inherent problems (lack of detail for one), but is another indicator of what we can learn from Google. Most important to me, the case provides an example of what it means for search engines to capture this information, because it demonstrates to the public at large (not just people who think about data all day) how the information can be used. As more information is collected about us, search engine data provides an imperfect mirror onto our society, previously known only to psychiatrists and priests.

From the New York Times, a piece about Predictably Irrational from Dan Ariely. I’m somewhat fascinated by the idea of our general preoccupation with holding on to things, particularly as it relates to retaining data (see previous posts referencing Facebook, Google, etc.)

Our natural tendency is to keep everything, in spite of the consequences. Storage capacity in the digital realm is only getting larger and cheaper (as its size in the physical realm continues to get smaller), which only seeks to feed off this tendency further. Perhaps this is also why more individuals don’t question Google claiming a right to keep messages from their Gmail account after the messages, or even the account, have been deleted.

Ariely’s book describes a set of experiments performed at M.I.T.:

[Students] played a computer game that paid real cash to look for money behind three doors on the screen… After they opened a door by clicking on it, each subsequent click earned a little money, with the sum varying each time.

As each player went through the 100 allotted clicks, he could switch rooms to search for higher payoffs, but each switch used up a click to open the new door. The best strategy was to quickly check out the three rooms and settle in the one with the highest rewards.

Even after students got the hang of the game by practicing it, they were flummoxed when a new visual feature was introduced. If they stayed out of any room, its door would start shrinking and eventually disappear.

They should have ignored those disappearing doors, but the students couldn’t. They wasted so many clicks rushing back to reopen doors that their earnings dropped 15 percent. Even when the penalties for switching grew stiffer — besides losing a click, the players had to pay a cash fee — the students kept losing money by frantically keeping all their doors open.

(Emphasis mine.) I originally came across the article via Mark Hurst, who adds:

I’ve said for a long time that the solution to information overload is to let the bits go: always look for ways to delete, defer, or otherwise avoid bits, so that the few that remain are more relevant and easier to handle. This is the core philosophy of Bit Literacy.

Put another way, do we need to take more personal responsibility for subjecting ourselves to the “information overload” that people so happily buzzword about? Is complaining about the overload really an issue of not doing enough spring cleaning at home?

A New York Times article from February about the difficulty of removing your personal information from Facebook. I believe that in the days that followed Facebook responded by making it ever-so-slightly possible to actually remove your account (though still not very easy).

Further, there is the network effect of information that’s not “just” your own. Deleting a Facebook profile does not appear to delete posts you’ve made to “the wall” of any friends, for instance. Do you own those comments? Does your friend? It’s a somewhat similar situation in other areas—even if I chose not to have a Gmail account, because I don’t like their data retention policy, all my email sent to friends with Gmail accounts is subject to those terms I’m unhappy with.

Regardless, this is an enormous issue as we put more of our data online. What does it mean to have this information public? What happens when you change your mind?

Facebook stands out because it’s a scenario of starting college (at age 17 or 18 or now even earlier), having a very different view of what’s public and private, and that evolving over time. You may not care to have things public at the time, but one of the best things about college (or high school, for that matter) is that you move on. Having a log of your outlook, attitude, and photos to prove it that is stored on a a company’s servers means that there are more permanent memories of the time which are out of your control. (And you don’t know who else beside Facebook is storing it—search engine caches, companies doing data mining, etc. all take a role here.) Your own memories might be lost to alcohol or willful forgetfulness, but digital copies don’t behave the same way.

The bottom line is an issue of ownership of one’s own personal information. At this point, we’re putting more information online—whether it’s Facebook or having all your email stored by Gmail—but we haven’t figured out what that really means.